Duffy Research Group

My research group has both basic and applied experimental research projects. On the basic research side we are involved in discovery based science. We design, simulate, build and test instruments that have unique abilities to probe the underlying quantum mechanical dynamics of gas phase chemical reactions, a field known as Molecular Reaction Dynamics.

Our particular focus is on using high frequency microwaves to probe the rotational transitions of product molecules. On the more applied side, we are attempting to create a mass spectrometer-like instrument that will, among other things, identify and separate molecular isomers by the strength of their dipole moments.

Our dream is to create the next indispensable analytical instrument, where in addition to identifying isomers it will yield invaluable molecular shape information through dipole moment measurements which are sensitive to subtle conformational changes. Please see the research tab for progress on both projects and please consider joining or collaborating with us!

Research

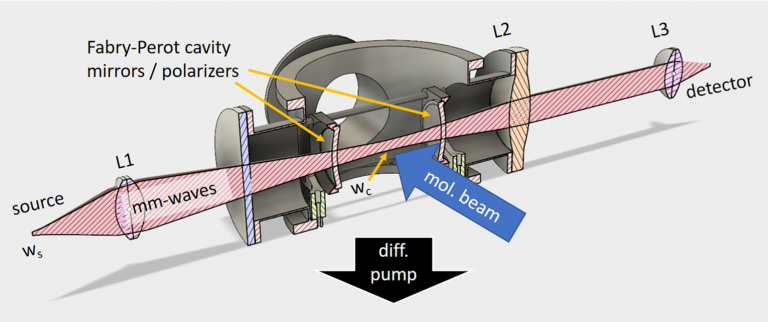

While molecular beam experiments are ideal for generating and studying transient species, low number densities and short pathlengths require highly sensitive spectroscopic methods. Unfortunately, in the THz / sub-THz region, the lack of strong sources combined with relatively insensitive detectors significantly impacts sensitivities. In the optical and Near-IR, fluorescent photon counting is possible, while in the longer microwave and RF regions, exquisitely sensitive heterodyne techniques are available. Not only are the sources and detectors better in these other electromagnetic regions, they may also be combined with cavities to dramatically increase the effective sample pathlengths, e.g., Cavity Enhanced Absorption Spectroscopy. Robustly coupling radiation in and out of cavities has proven to be problematic in the THz / sub-THz region due to the lack of high reflectivity / partially transmissive concave dichroic mirrors at these wavelengths. A partial solution has been to employ multipass or unconventional cavity geometries.

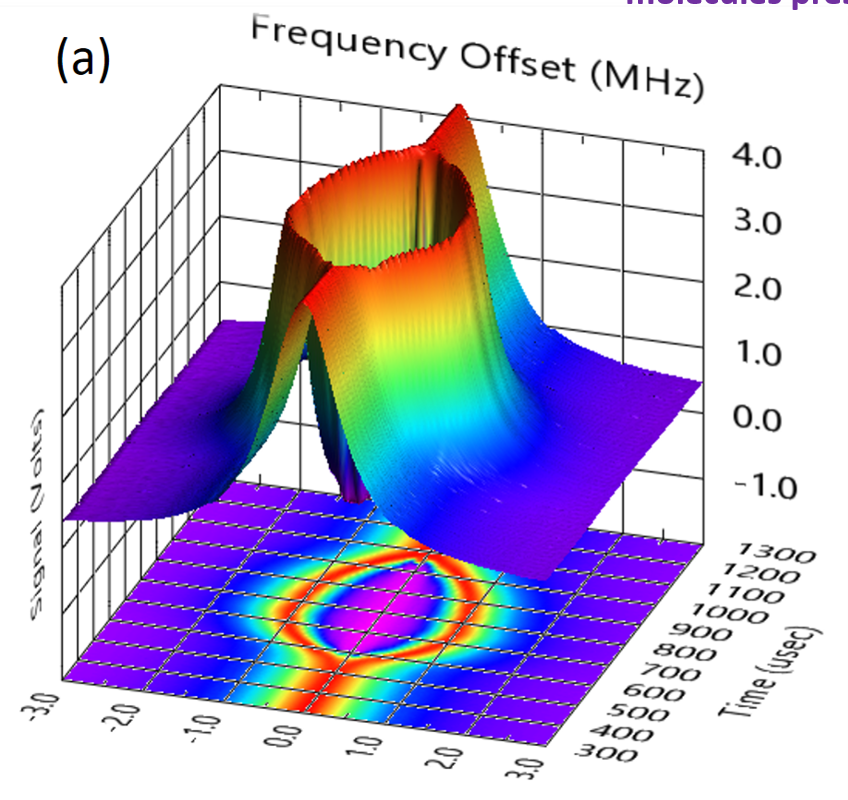

We have demonstrated that it is possible to create a pass-through confocal Fabry–Pérot resonator at sub-THz wavelengths; the novelty being the simple conventional layout. To do this we have created, the equivalent of dichroic mirrors with concave wire-grid polarizers on a supporting plastic substrate. The resulting signals are beautiful and dramatic (see Fig. 1). We obtain cavity Qs on the order of 100,000, a 70-fold sensitivity increase and use it to demonstrate the detection of ClO radicals and even the weak magnetic dipole allowed transitions of O2 near 60 GHz. As the signals are coherent, we model the line shapes using a modified Flygare et al. solution to the Optical Bloch equations.

Figure 1, Reaction coordinate and transition state. Product state distributions (vibration, rotation, etc.), hint at the transition state geometry

Chemical reaction mechanisms are of central importance to organic, inorganic, and biochemistry. Armed with a solid understanding of the mechanisms behind chemical reactions, chemists are able to predict and design syntheses of new and important compounds. However, despite of the importance of the reaction mechanism, the transition state is often poorly characterized experimentally.

Something of a misnomer, the transition state is not so much a “state” as it is a point along its path to products. In most cases, it represents some restricted geometry, through which a molecule must transform on its way to products. For example, in Figure 1 to the right, the transition state lies at the top of a barrier between reactants and products.

While transition states play such an important role in chemistry, very little direct evidence of their structure exists due to their inherently transient nature. Historically, researchers were limited to performing kinetics experiments that could, at best, provide supporting evidence for a proposed mechanism. Over the last 40 years, however, physical chemists / chemical physicists have become increasingly sophisticated in their ability to probe chemical transition states at an ever increasing level of detail.

The field of research which has grown out of these studies is known as “molecular reaction dynamics.” It’s goal is to understand chemical reactions at their most fundamental, quantum mechanical level of detail. Great advances have been made within the field both experimentally and theoretically and it is now possible, for some small molecular systems, to completely characterize a reaction from the initial quantum state of the reactants to the final product state distributions. With the advent of femtosecond spectroscopy, even the transition state may be probed as the reaction unfolds.

In my research, rather than trying to probe the transitions state directly, we attempt to learn as much as possible about the transition state structure through a detailed analysis of the quantum states of the product molecules; much like a police officer analyzes the debris of an accident to determine what happened. Unlike more traditional methods for doing this, such as Laser Induce Fluorescence (LIF), we do this with pure rotational spectroscopy, as outlined in the “research overview” section.

(The easy way to generate millimeter wavelength radiation)

This section describes the method we use to generate millimeter and sub-millimeter wavelength radiation (mm/submm-waves). For a discussion of the frequency regions we use and why (click here). In our lab, we can currently cover the region from 50-330 GHz. There are other ways to do this, but this is the simplest and most flexible way.

The Source:

The “millimeter-wave source modules”, depicted above, are from Agilent Technologies (Models: 83557A and 83558A covering 50–75 GHz and 75–110 GHz, respectively); similar systems are also available from Anritsu Corporation. Because of their appearance, the Agilent source modules have been nicknamed “Armadillos” by network analysis engineers. Like the earlier cat-whisker Schottky diodes, these new sources are also microwave multipliers. However, instead of the Schottky diode junction being formed between a sharpened wire cat whisker and crystal, the new commercial multipliers are made from planar solid-state Schottky diode arrays. Not only are they much more robust than the homemade diodes, but the new sources are also several orders of magnitude more powerful, providing power output levels on the order of 1 mW. In addition, the power and frequency stabilization electronics are seamlessly integrated with standard microwave synthesizers. The system requires little or no user intervention and, when connected to a highend microwave synthesizer such as the Agilent HP83623B (with option 008; 1 Hz resolution, may be operated in CW mode, modulated AM or FM, swept, or pulsed.

Various third party millimeter-wave amplifiers (from Spacek or Terabeam) and multipliers (from Virginia Diodes) may in turn be added to the armadillos, further pushing their outputs well into the submm-wave region. In our lab, sets of commercial solid-state millimeter-wave amplifiers and multipliers are used to extend the range to 330 GHz. With the exception of small gaps between 130–150 and 220–225 GHz, output power levels across the entire range on the order of 1 mW are achieved. Multipliers up to 1.7 THz are now commercially available.

The Detector:

The transient mm/submm-wave absorption signal is detected with a liquid-helium-cooled InSb hot-electron bolometer chip made by QMC Instruments Ltd. (Model: QFI/X) and housed in a liquid-nitrogen/helium Dewar (Infrared Laboratories Inc. Model: HDL-5) with a 1 in. diameter entrance window and internally mounted millimeter-wave feedhorn, known as a Winston cone. For increased sensitivity, the active area of the 5×5 mm2 InSb detector chip has a serpentine layout, earning it the nickname “toaster” by millimeter-wave engineers. This type of bolometer is sensitive to frequencies in the range of about 60–900 GHz, and has a measured system optical NEP of 7×10−13 WHz−1/2 at about 1.5 K, a responsivity of 5 kV/W, and a response time on the order of a third of a microsecond (i.e., 3 MHz). An ultra-low noise preamplifier (Infrared Laboratories Inc. Model: UNL-6) is used to amplify the transient signals without adding noise.

My students and I have designed, built and tested a unique instrument for probing molecular reaction dynamics via pure rotational spectroscopy. The technique takes advantage of high frequency microwave sources in the millimeter and sub-millimeter wavelength region to probe the products of gas phase reactions. The ultimate goal of this research is to deduce the molecular electronic states involved in the transition state of a chemical reaction by measuring the speed, direction and internal energy of the products, much the same way an officer attempts to determine the cause of a car accident by studying the wreckage. Product molecules may be formed in a wide variety of rotational, vibrational, and electronic (rovibronic) states. Measuring and predicting these distributions is the primary way that physical chemists attempt to understand the nature the transition states of gas phase reactions. The ultrahigh resolution afforded by the microwave technology has allowed us to probe these product state distributions with unprecedented hyperfine detail.

These sorts of experiments involve a variety of high-tech devices and tools including high powered lasers, oscilloscopes, vacuum chambers and pumps, supersonic molecular beams, as well as microwave sources and liquid helium cooled detectors. We have performed single molecular beam photodissociation experiments to emulate UV induced reactions implicated in ozone depletion and more recently we have begun crossed molecular beam experiments to study bimolecular reactions of reactive radical species such as excited oxygen (1D) atoms. We also have a tangentially related project to slow molecular beams using a microchip based Stark decelerator. We are designing this chip with the ultimate goal of producing ultracold molecules for the study of ultracold chemistry.

What are mm-waves and why do we use them?

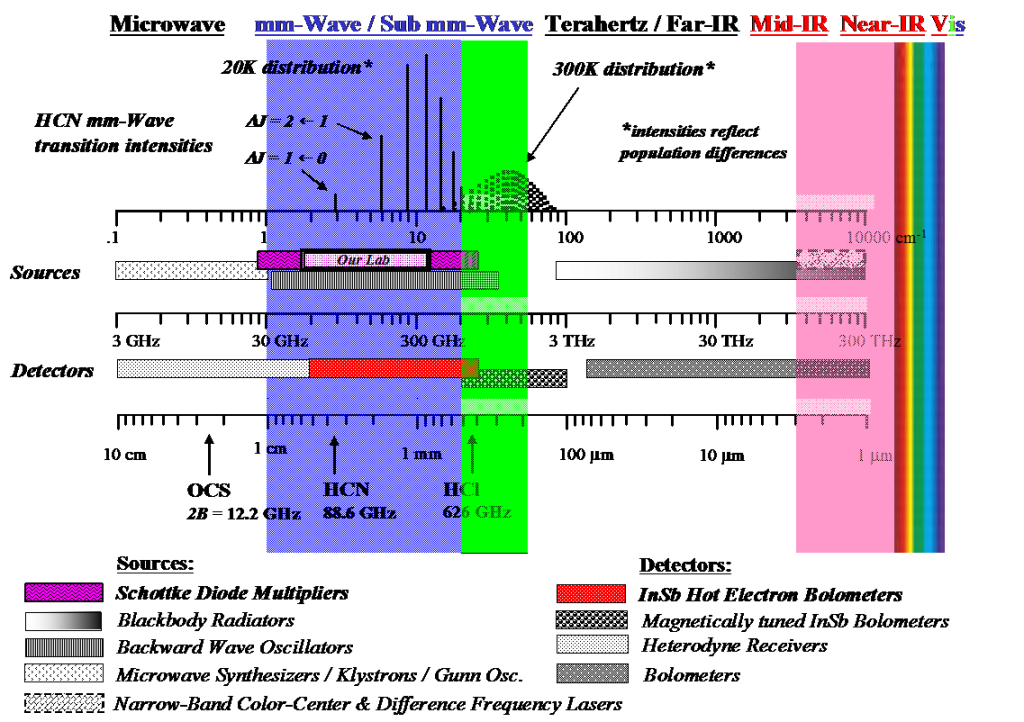

In our research, we use pure rotational spectroscopy to probe reaction dynamics. Oddly enough, while rotational spectroscopy is arguably one of the simplest and highest resolution forms of spectroscopy, it is also one of the most underutilized and least known forms of spectroscopy. While spectroscopists have been conducting high resolution studies of small molecules with these wavelengths for decades, the technology to generate and detect the appropriate radiation (microwave, millimeter wavelength, submillimeter wavelength, and terahertz radiation, see figure above) has required highly specialized knowledge of microwave and radio frequency technology. As a result, an unnatural divide has existed between low frequency forms of spectroscopy and so called, “optical” forms of spectroscopy such as infrared, visible, and UV.

Recently, new simple-to-implement technology has become available for generating millimeter / submillimeter wavelength (mm/submm-waves) radiation (see section on “What’s an Armadillo?”). This technology is so simple to use that it can now be easily integrated into more complicated, “reaction dynamics” sorts of experiments. Furthermore, at these frequencies it is actually better to propagate the radiation through “free space”, rather than with waveguides. This allows the use of plastic lenses to pass the radiation through the experiment.

We take advantage of already assigned and cataloged transition frequencies (see JPL and Cologne databases) of small molecules to determine the quantum state distribution of the reaction products. In addition to the ultrahigh resolution afforded by the technology, the spectroscopy may be used to probe a wide variety of product molecules. The gross selection rule for pure rotational spectroscopy is simply that the molecules are polar. This means the products / parent molecules may be ions, radicals, neutrals, transient intermediate, or even clusters.

The figure above gives the dominant sources and detectors used between microwave and IR wavelengths as well as examples of transition frequencies and intensities of HCN at supersonic molecular beam and room temperatures. The technologies are constantly changing, and as a result, the figure should be considered a rough guide; difference frequency IR techniques now routinely get into the low Mid–IR and THz sources are a hot area of research. Commercially available multiplier technology from Virginia Diodes now exists up to 1.7 THz (green region below).